Seven magnificent years have now passed since the launch of the WS Havelock Global Select Fund. In that time, investors in the fund received a compound average annual return of 8.4%. This means that we have “beaten” both the average fund in the Investment Association Global Sector, and the largest available passive “value” ETF for UK investors. The fund was also “up” in each full calendar year since inception.

Whoop!

However, and there is a however, it has not been sufficient to outperform the MSCI World index. Our “value” style of investing, our greater focus on mid and small-capitalisation companies, and our lower weight to the US markets have all created a headwind in this regard. We have never owned any of the “Magnificent Seven” companies in the fund, and they have been the driving force behind much of the MSCI World’s strong performance.

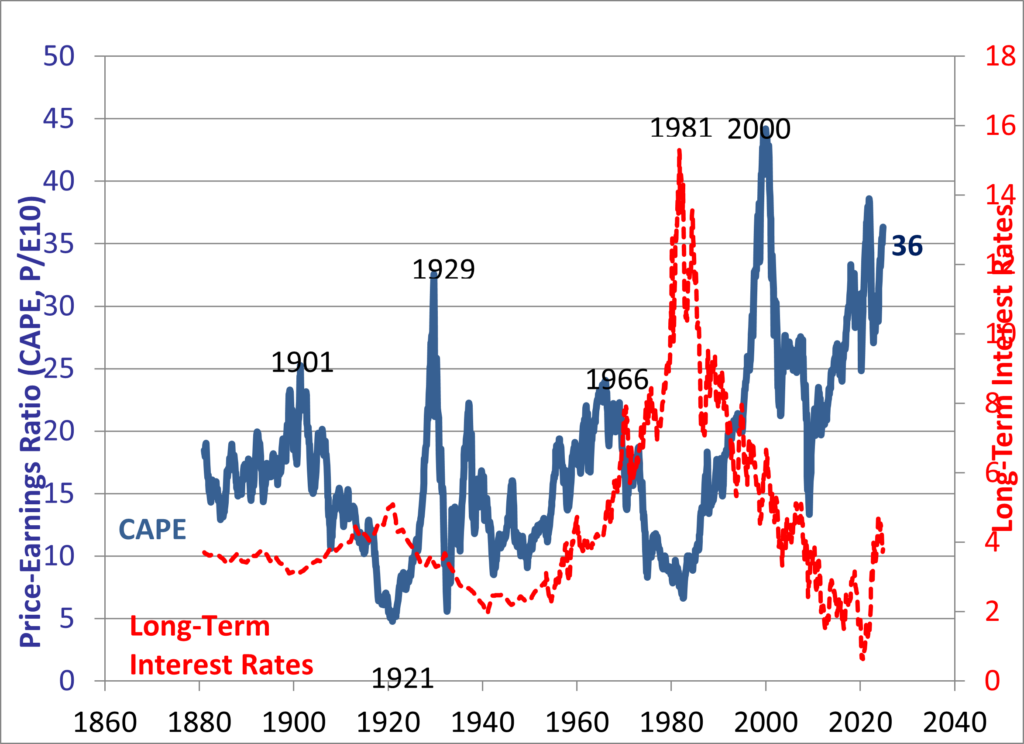

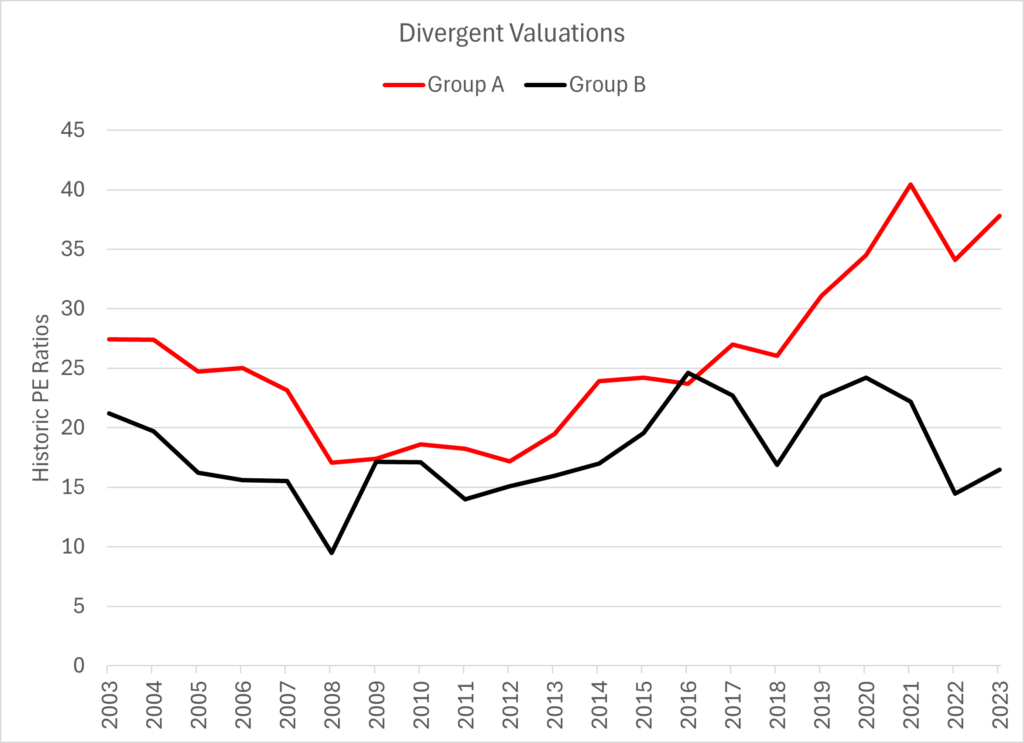

The chart below displays the total market capitalisation and earnings (or profits) of the Magnificent Seven as a percentage of the MSCI World. This shows how these seven companies now make up around 24% of the index by weight (blue), despite their share of company earnings only being around 15% (black).

The chart also shows the seven companies’ share of free cashflows, which is defined as the cash that a business generates less its capital expenditures. For those readers who are not accounting “wonks”, you can think of this as an alternative measure of the “spoils” that a company generates for its shareholders.

What we would really like to know is if these seven companies will “grow into” their valuations, as they have done in the past. They are mighty businesses, and their outsized weights in the index would be justified by them continuing to grow earnings and cashflows at a faster pace than other companies.

The catch is that as the seven get larger, further growth becomes harder to come by. Much hope is now placed on “Artificial Intelligence” as their next frontier for growth, and the investments that they are making in it are causing large increases in capital expenditure in what have historically been “capital light” businesses.

The chart above shows how these companies historically represented a much higher share of free cashflows, than earnings, in the index. As they have increased their capital expenditures in recent years this gap has narrowed. Put differently the cash they generate for shareholders appears to be increasing more slowly than their profits as calculated by the rules of accounting.

Opinions on if we are in the midst of an “AI bubble” are divided. Even if we take an AI productivity boom as certain, it remains unclear if the Magnificent Seven will be the main beneficiaries. I do not have the answers to these questions, but I do know that many investors are heavily exposed to them.

These companies feature heavily in many investors’ portfolios. For them to provide above average investment returns it needs the companies’ earnings to not just grow, but to grow at a rate above what is already “reflected in the price”. If growth undershoots these expectations, it will be likely that their share prices will fall. I cannot know if this will happen but see it as more likely than not.

I suspect that the extent to which these companies are owned by investors is at this stage more a product of a “safety in numbers” mentality, than strong convictions on their future growth rates. This is precisely the situation that investors in passive indices find themselves in. However, the lower your confidence that they can grow above the high rates already “priced in”, the less your portfolio should be exposed to them. This is where we come in!

In the lifetime of the fund, it has increasingly been seen as “different and useful”. Different, because it is investing in corners of the market that are not well represented in the large indices or many (most?) other global funds. Useful, because we have demonstrated an ability to generate “better than average” results.

Whilst I cannot make any promises about future performance, we are committed to owning a portfolio that is “different”. I believe that this means we offer something of a “hedge” to our clients’ portfolios if the Magnificent Seven fall short of current high expectations.

Before signing off it just remains for me to say thank you to our clients for the confidence that they have shown in us. In the years ahead we will continue to work hard to justify it. Although I can make no promises about performance, most of my net wealth is invested in the fund, and so we shall experience the highs and lows together.

Matthew Beddall

CEO & Fund Manager, Havelock London Ltd