I felt that I should share some thoughts and observations on the large fall in equity markets that we saw in the first week of the second quarter of 2025.

From my perspective it looks like the type of panic that is to be periodically expected in markets, and of the type that I have seen many times before. Our estimate of the fund’s “beta”, or sensitivity to a short-term fall in markets, was about 1x, and so far, this looks reasonably accurate. For many of the mid-caps we follow the price action looks relatively detached from any reasonable interpretation of tariff threats, and I believe that the decline has been exacerbated by leveraged investors making a “mad rush for the exits”.

The Financial Times reported* on the observations of hedge fund broker, Morgan Stanley, that Thursday 3rd April was “the worst day of performance for US-based long/short equity funds since it began tracking the data in 2016”. It also said that “the magnitude of hedge fund selling across equities on Thursday was in line with the largest seen on record”. This suggests that price moves have been driven by a panicked liquidation, more than a calm analysis of the facts.

Although we do not believe in trying to make short-term forecasts, my “best guess” is that we will see a “relief rally” as the worst of the liquidation passes. I think the true implications of the changing world order will take longer to become clear, and hence impact market prices. These price falls are certainly not a reason why we would start liquidating our own holdings, rather we look to cautiously make opportunistic changes to take advantage of others’ panic.

An example of this is our large holding in Air Lease that saw a 16% price fall in the space of two days. Air Lease buys aircraft and rents them to airlines, and at face value the tariff on importing planes into the US might seem like bad news. However, much of the company’s business is outside the US. More importantly, they have written into all their contracts that it is the Airline customers who bear responsibility for all tariff-related costs. Given the price fall I would guess that this is not widely understood.

In the final few days of March, the company had announced a partial settlement with their insurers from the aircraft that they have had “confiscated” in Russia. This will reverse part of their previous write off and increases the likelihood that the remaining unsettled claims will pay out in the company’s favour. The impact of the initial cash payments from insurers is that the “book value” of the company will increase by around 4%.

So, arguably, in the space of a couple of days the company moved to be 20% cheaper than it was previously, with no material first-level impact from tariffs. The company continues to own scarce assets that are in high demand. If consumer demand for flying softens, then it will be the oldest aircraft that airlines idle due to the cost of maintaining them, not the comparatively new planes that Air Lease owns.

I share this story as an example of what we have been seeing “at the coal face”, and the opportunities that the panic is potentially creating.

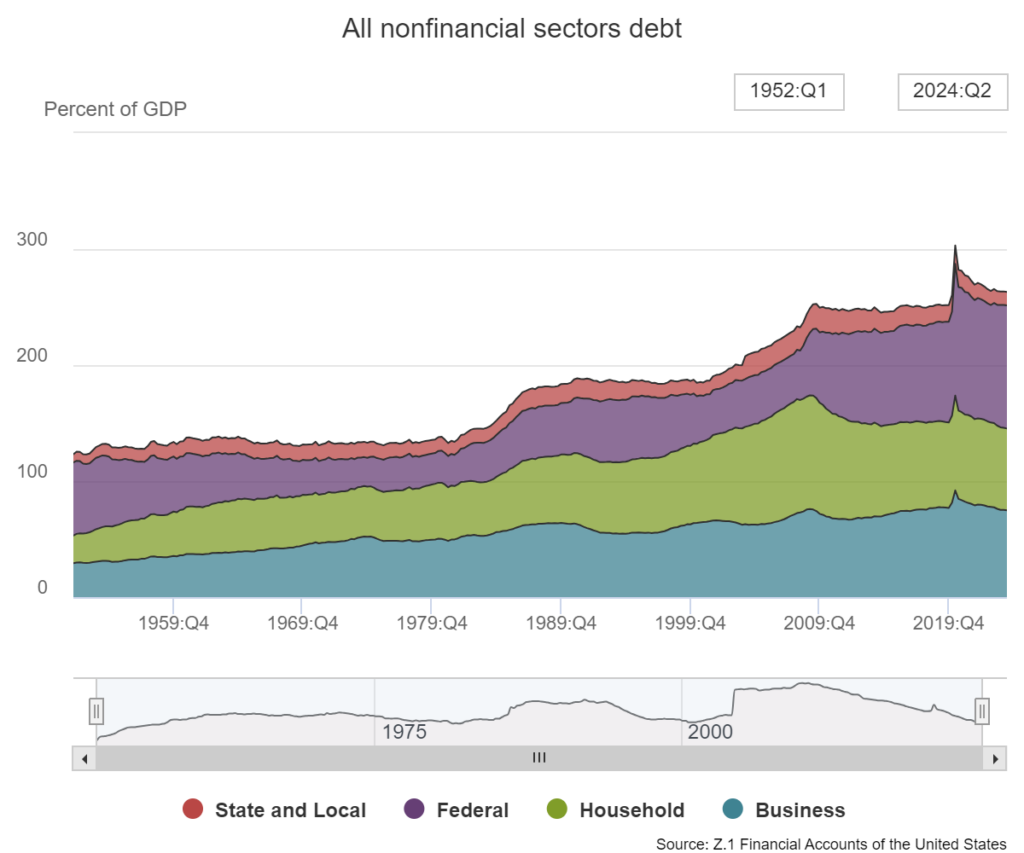

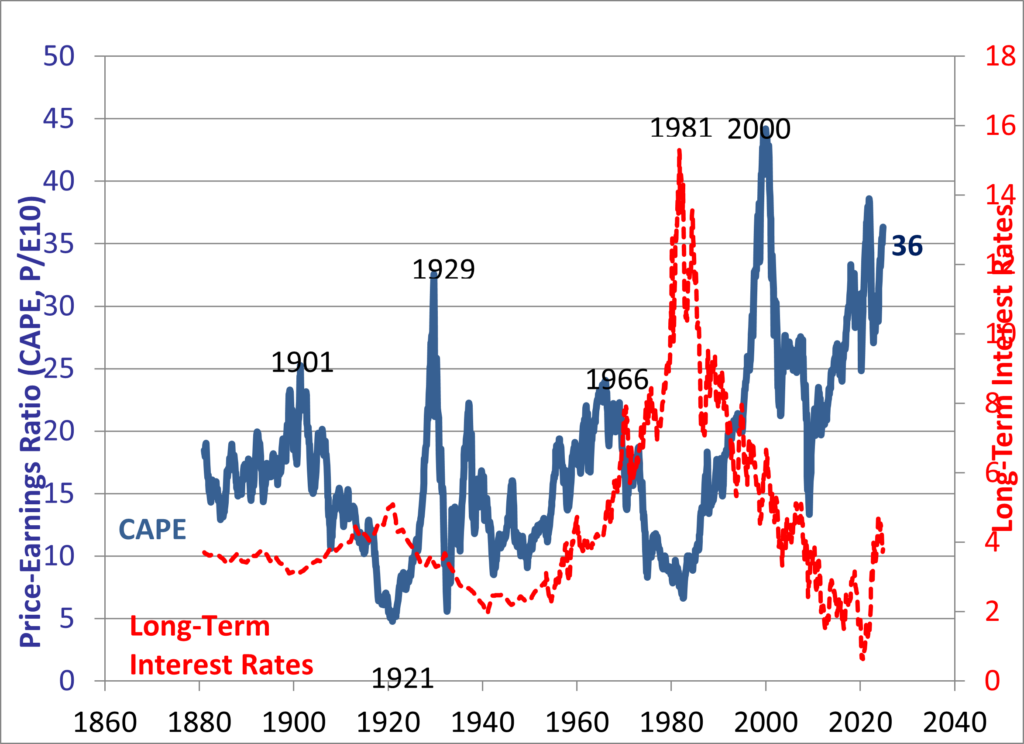

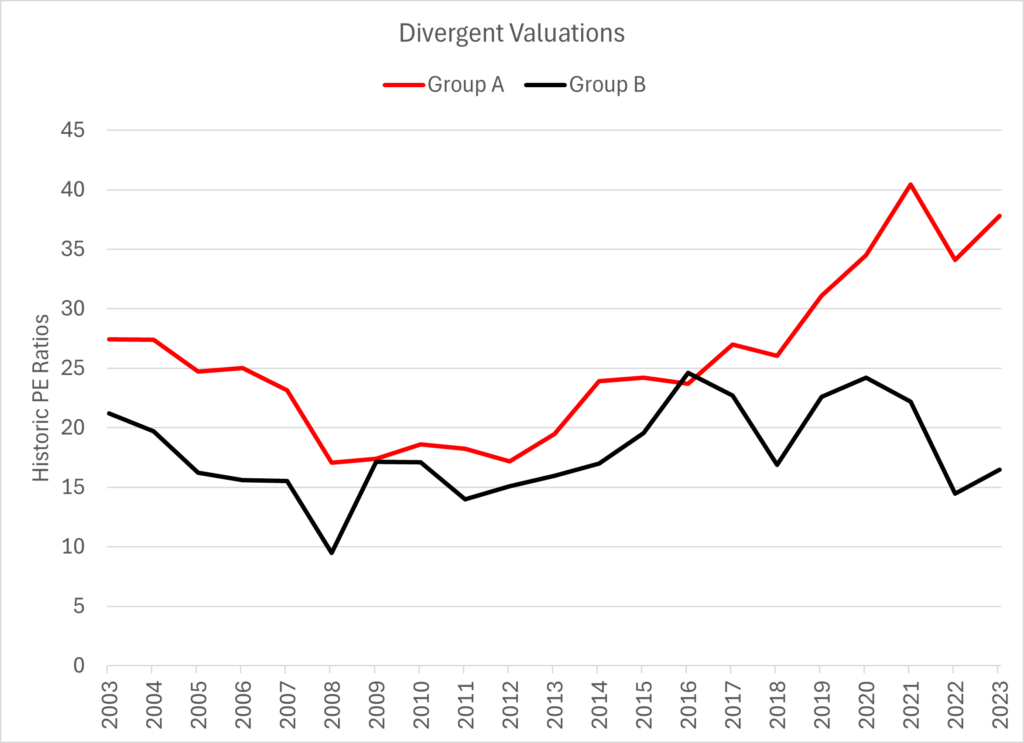

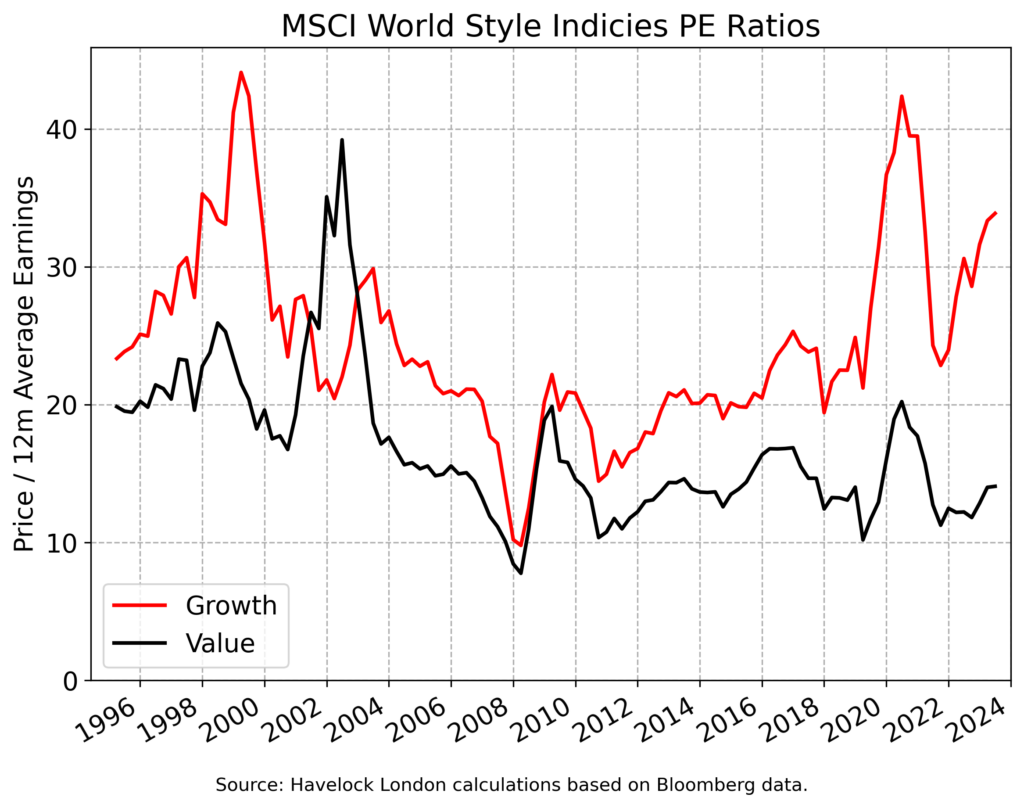

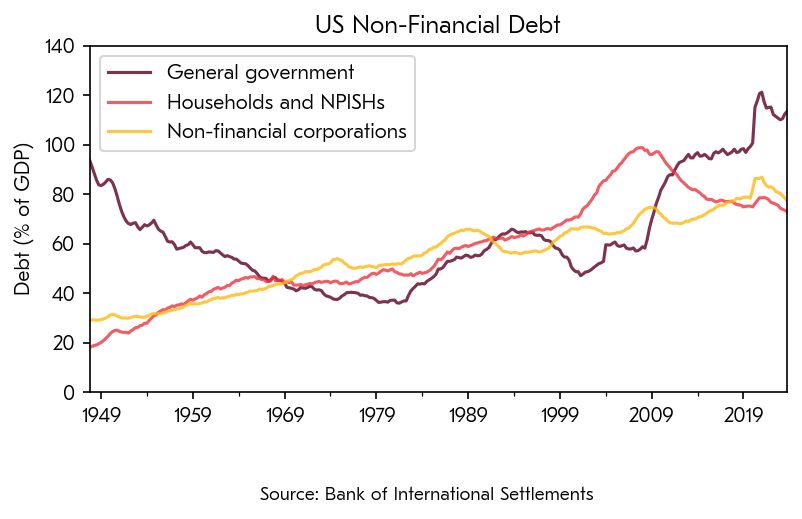

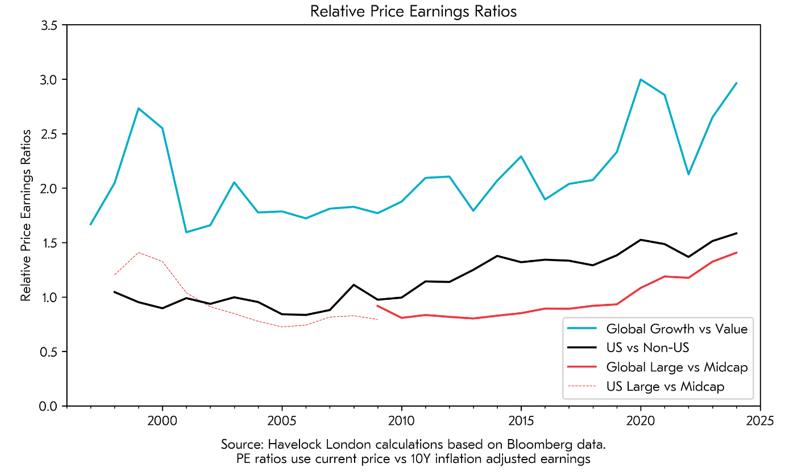

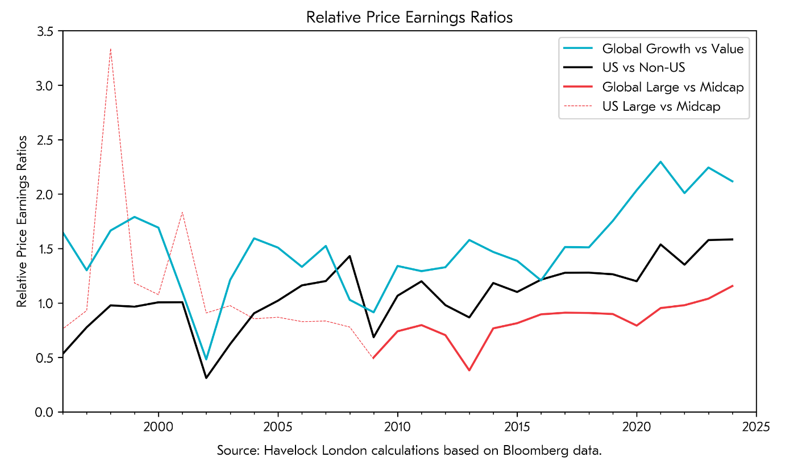

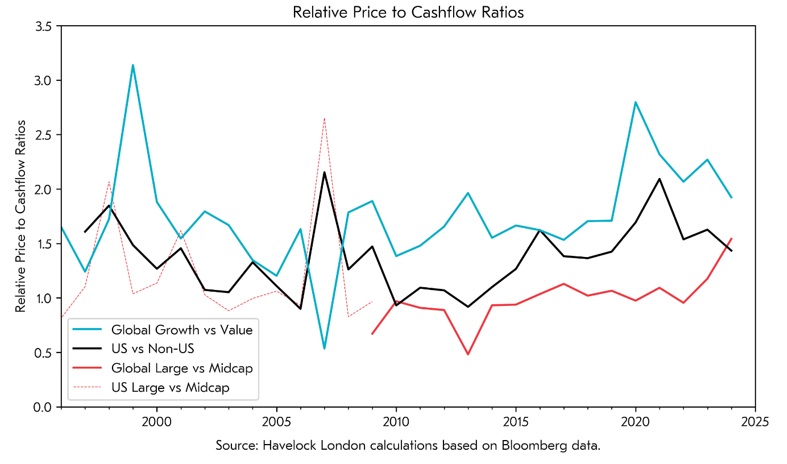

I do not know if this panic will prove short-lived or not. However, I think investors face the dual threats of higher inflation, due to the size of government debts, and weaker corporate earnings, due to a subdued economy. In this environment owning cash or bonds risks losing purchasing power, whilst owning equities priced for high growth risks disappointment. I see the modest valuations and robust balance sheets of the companies we own as both a source of defence and opportunity. In the years following the dot-com crash, and the collapse of the “Nifty Fifty” in the 1970s, value investing delivered a healthy outcome for investors. I cannot know if this will repeat, but it evidences the argument for “value” in this environment.

At Havelock we are focusing all our efforts on running one fund in which we have our own money invested. We have had six consecutive calendar years of positive returns, as well as 18 out of 26 quarters. Our company is both profitable at its current size and has around 3 times its required regulatory capital in reserves. This is all to say that we feel well prepared for whatever comes next.

Matthew Beddall

CEO, Havelock London

* https://www.ft.com/content/8ba439ec-297c-4372-ba45-37e9d7fd1771