As of writing the Nasdaq index of “growth” stocks has fallen by 27% in the year to date*. Why has it fallen by so much and does it mean there are some bargains to be had?

The popular narrative for why we have seen heavy price falls in many “growth” stocks is that it was caused by investors changing their expectations about the path of future interest rates. I will (reluctantly) explain this for those readers who have been living in a cave and not heard it before. The logic is that investors were prepared to pay high prices for high growth businesses, because low interest rates meant they earnt less from more certain near-term investments, and so profits in the distant future became more appealing.

The appeal of this narrative is that it involves maths and things called “discounted cash flows” – all of which helps make it sound clever and objective. Were lots of investors really sat around their pocket calculators, carefully figuring out the impact of low interest rates on company profits in the distant future? I think not.

As an explanation it requires investors to have been confident about (a) companies continuing to grow profits and (b) interest rates remaining low. It follows that this popular narrative is really just saying that people were buying stocks based on speculative views about the future. The clever sounding maths provides a veneer of respectability that I don’t think is deserved.

I, personally, prefer the narrative that the large falls in growth stocks that we have witnessed are the result of investors being now driven more by the fear of losing money than the greed of making it. Admittedly, my narrative involves animal spirits and not maths, and so is perhaps less palatable to many end clients of the investment industry.

The important question going forward is if the price falls in growth stocks mean that there are bargains to be had. This also conveniently provides me with the opportunity to use some maths and prove that I am not a complete luddite!

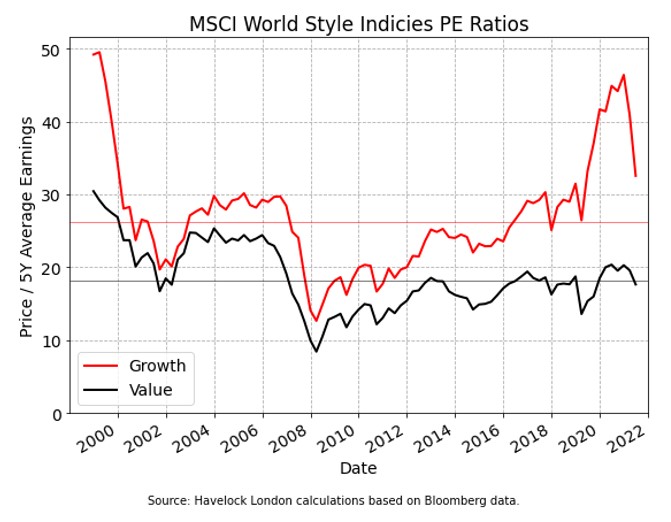

I made use of the MSCI World Growth and Value indices, that crudely divide companies into one of these two classifications. I calculated the price earnings (PE) ratio for each of the two groups of companies, where the earnings are the average of the last five years. The chart below shows this data, with the two horizontal lines showing the average (median) PE ratios for the entire period.

What does this chart tell us?

Based on price earnings ratios, the growth companies have been historically more expensive, but the extent to which this is true increased massively in the last three years. This means that despite the MSCI Growth index having already fallen by 27% this year*, it would require a further 24% drop for its price earnings ratio to be at its historic average. By the same token the value index is already at its historic average level.

It follows that I do not see evidence that this year’s price falls mean that yesterday’s stock market darlings, have automatically become no-brainer bargains. But I do see signs that the price falls are creating opportunity.

Our “quality value” approach to investing rests on the idea that a crude classification of companies as either growth or value is too simplistic. On a bottom-up basis, we see many companies that we judge as high quality now available to purchase at valuations that look undemanding versus history. Put simply I believe that there is a rich opportunity set, but that it is naive to think that everything that has fallen in price must be a bargain.

I will end by saying that despite my cynicism, narratives clearly do matter. They help us to understand the world around us and provide us with a sense of order and certainty in amongst the disorder and chaos. More than this, narratives help us to make decisions in the face of uncertainty, and nowhere is this truer than in investing. The problem with narratives though, is that we rarely get to find out if they are true. For this reason, I believe that the best investors remain humble about the extent to which they understand the world.

*Source: Bloomberg as at 20th May 2022