As the pandemic continues into its third year, many of us had to put our overseas holiday plans on hold again in 2021. Whilst it is sensible to hold off checking whether our swimming costumes still fit until after a January detox, there is no better time to check our investment exposures.

‘Only when the tide goes out do you discover who’s been swimming naked.’

Warren Buffett

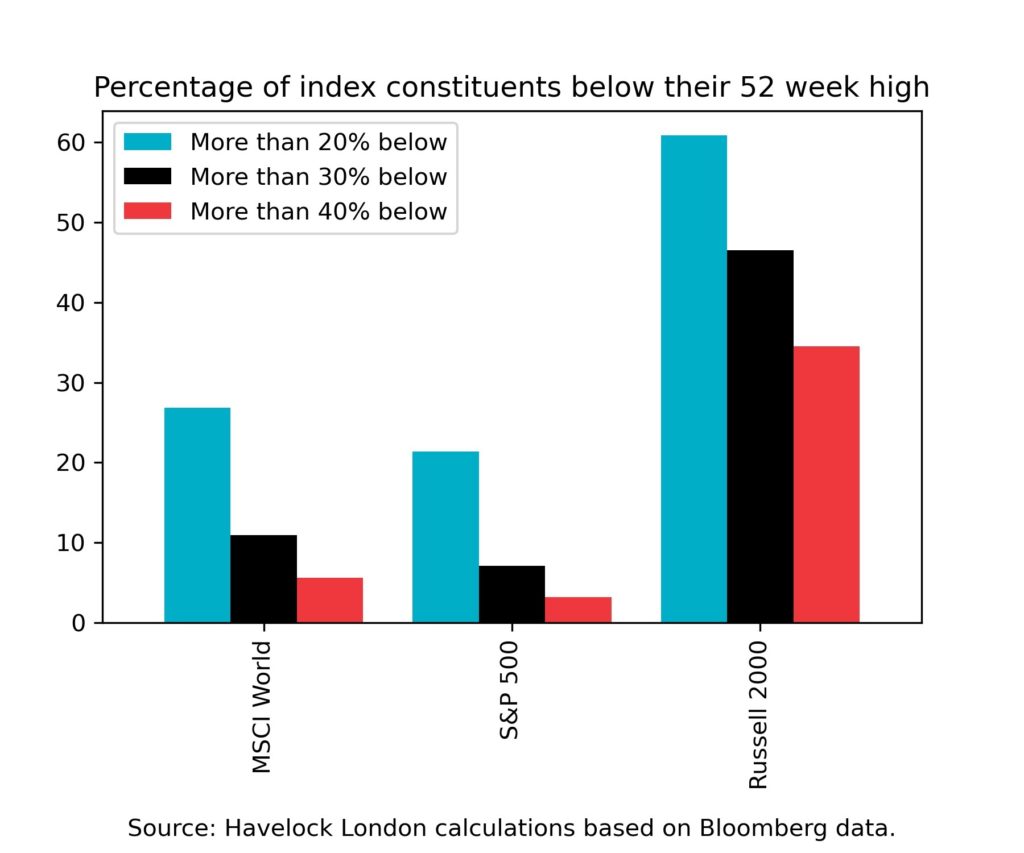

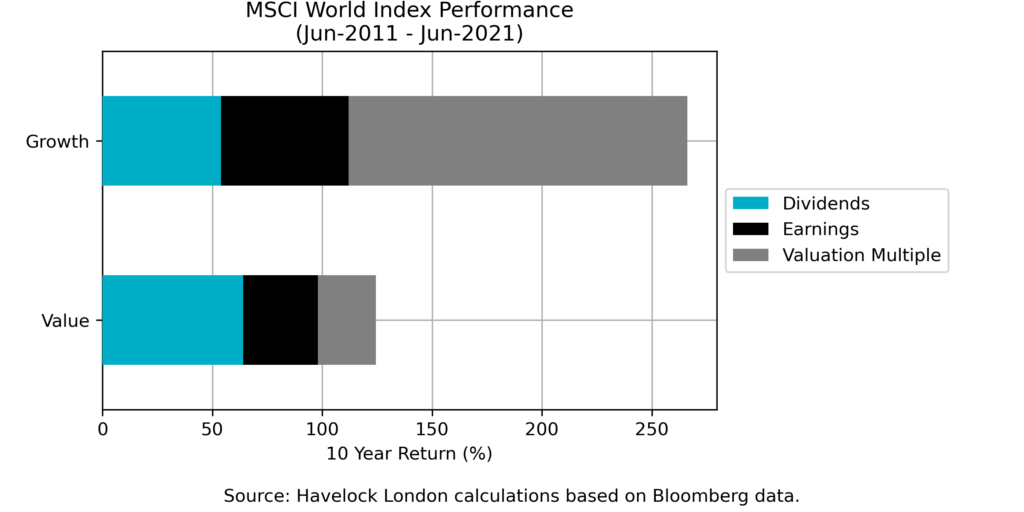

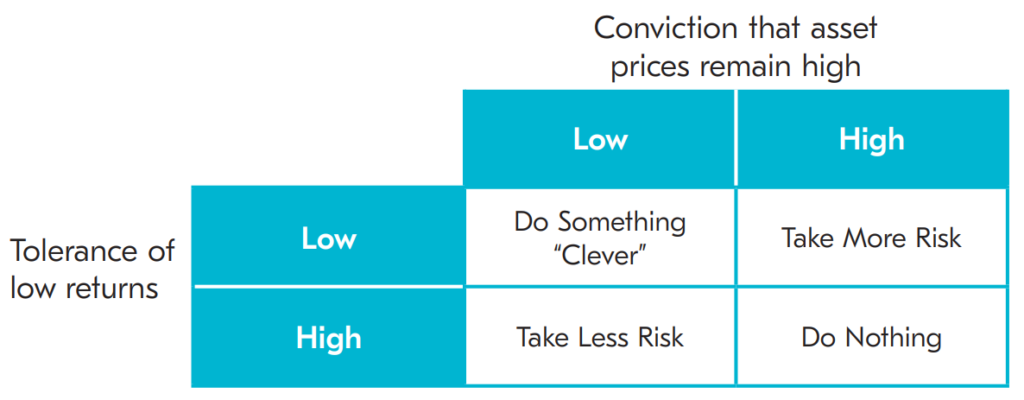

The above quote from Warren Buffett could apply to when the tidal wave of liquidity provided by the World’s Central Banks recedes, showing which investors were too reliant on it continuing. We believe that many investors could be found to have been consciously, or otherwise, overly exposed to three specific themes within equity markets; the US, the ‘growth’ style and a small number of large companies.

The US

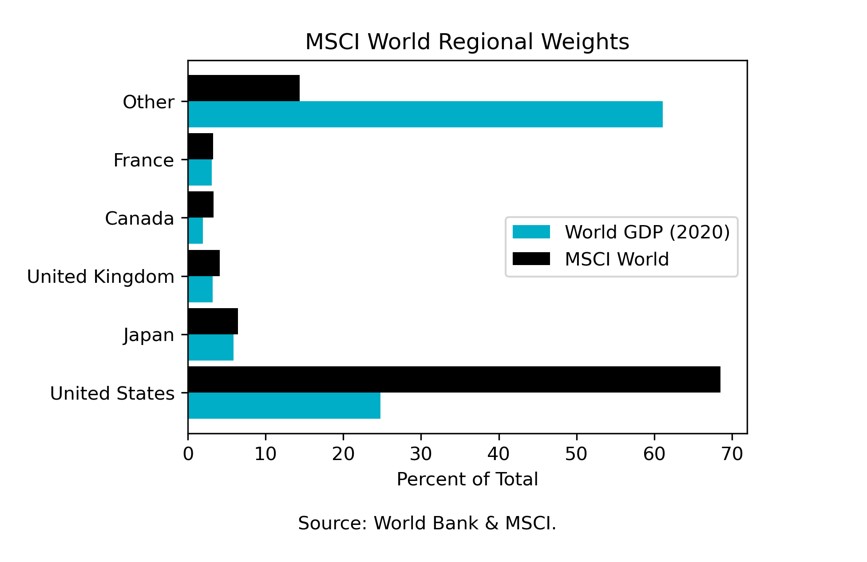

Without doubt, the US is home to many of the highest quality, most innovative and world-leading companies. The US weighting within the MSCI World Index stands as an eye-watering 69% as of 30th November 2021, but only represents circa 25% of 2020 World GDP as the chart below illustrates.

Anecdotally, Japan peaked at 44% of the MSCI World Index in the 1990s and sits at a paltry 6.5% as of the end of October 2021.

Is it the case therefore, that investors in the MSCI World Index, or global funds with a keen eye on their benchmark, are placing disproportionally high bets on the US continuing to outperform all other markets?

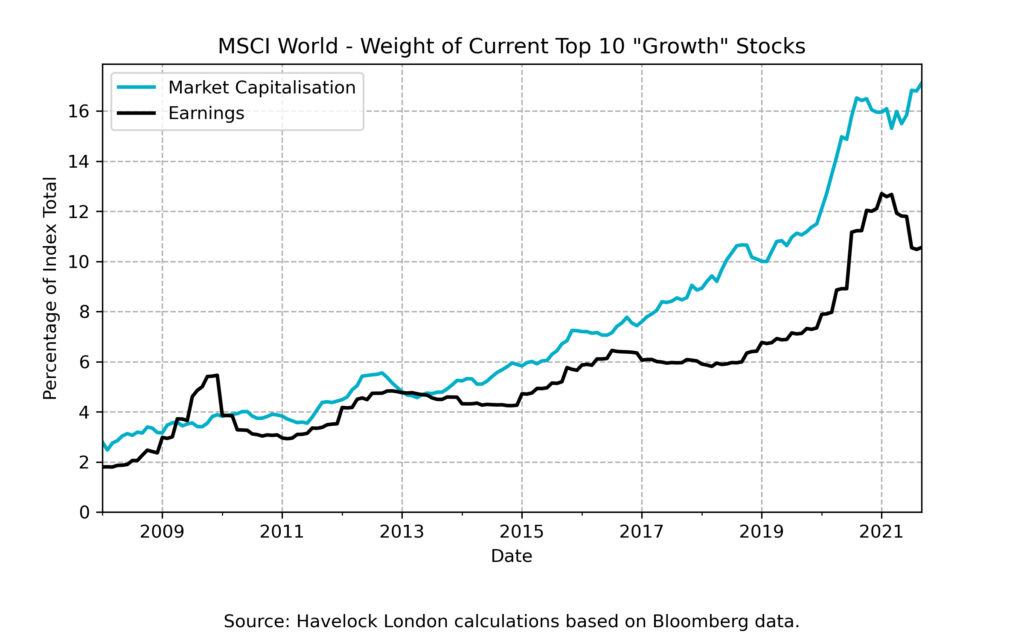

The ‘growth’ style

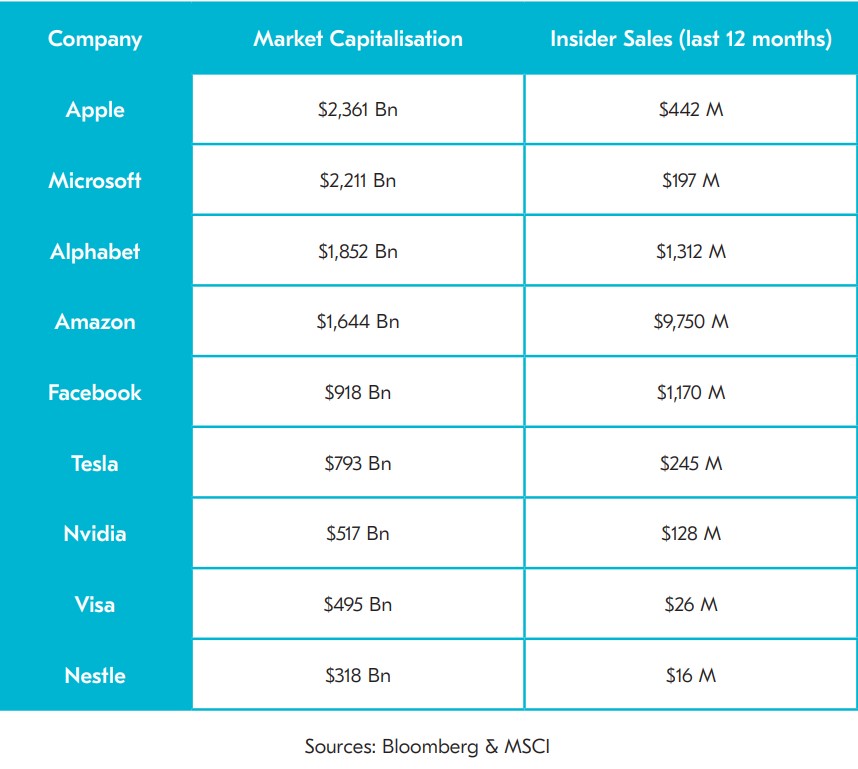

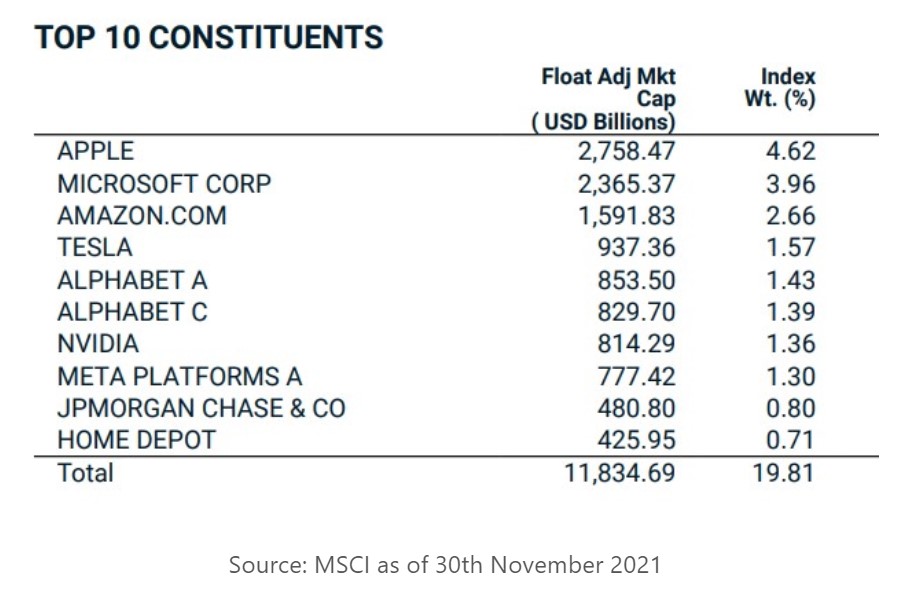

The top 10 company weights by market capitalisation of the MSCI World Index are shown in the table below:

They are all US listed companies, and the top 8 would be categorised as ‘growth’ stocks in the truest sense. We believe it is overly simplistic to categorise over 40,000 listed securities as either ‘growth’ or ‘value’, and to then assign specific characteristics to each category, such as ‘high-quality growth’ companies and ‘low-quality, zombie value’ companies. It is beyond doubt that ‘growth’ has significantly’ outperformed ‘value’ over the last ‘tech-ade’, but as shown in previous articles, the bulk of this outperformance has come from earnings multiple expansion. After a decade of outperformance, is it the case that investors are over-exposed to ‘growth’ relative to ‘value’, at the exact moment when it appears most expensive?

The same companies

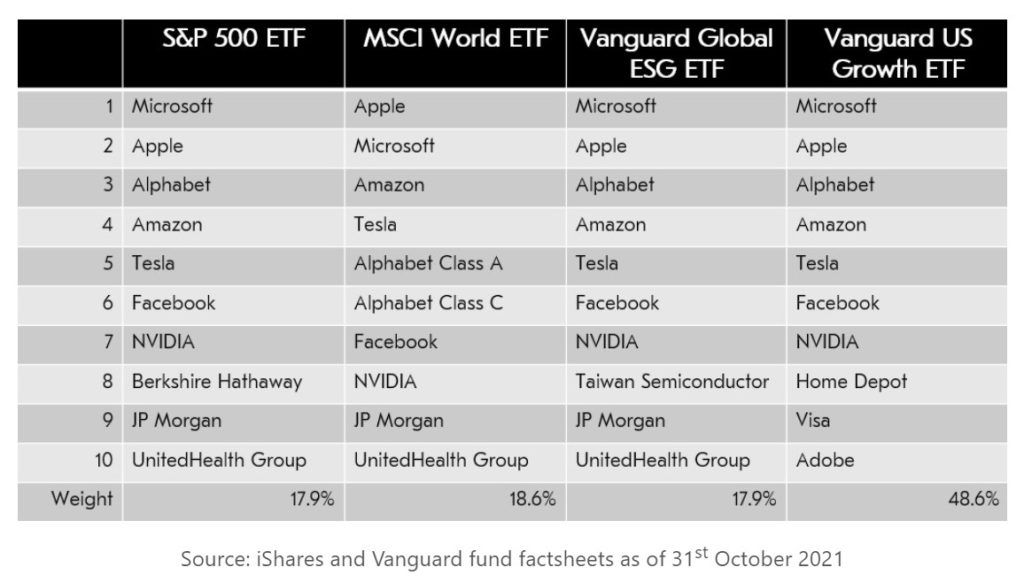

The top 10 constituents of the MSCI World Index (shown above) not only represent almost a fifth of this 1,555-stock index, they also represent circa 30% of the S&P 500 and frequently feature in top 10s of ‘growth’, ‘value’, global and regional funds alike. Increasingly, many of these companies have also been mainstays of active and passive funds branded ESG or Sustainable, as the table below illustrates:

Is it possible that investors’ portfolios aren’t as diversified as they may believe, as the same dominant, multi-trillion dollar mega-caps are appearing in an increasing number of products?

In summary, after the last ‘tech-ade’, would it be prudent for investors to consider if their portfolios are adequately diversified across regions, styles and companies, so that they won’t risk embarrassment should the tide go out?