I have written before about my concerns over the optimism that is required to justify the valuations of many popular “growth” stocks. The analysis that follows will further explain why I have these concerns.

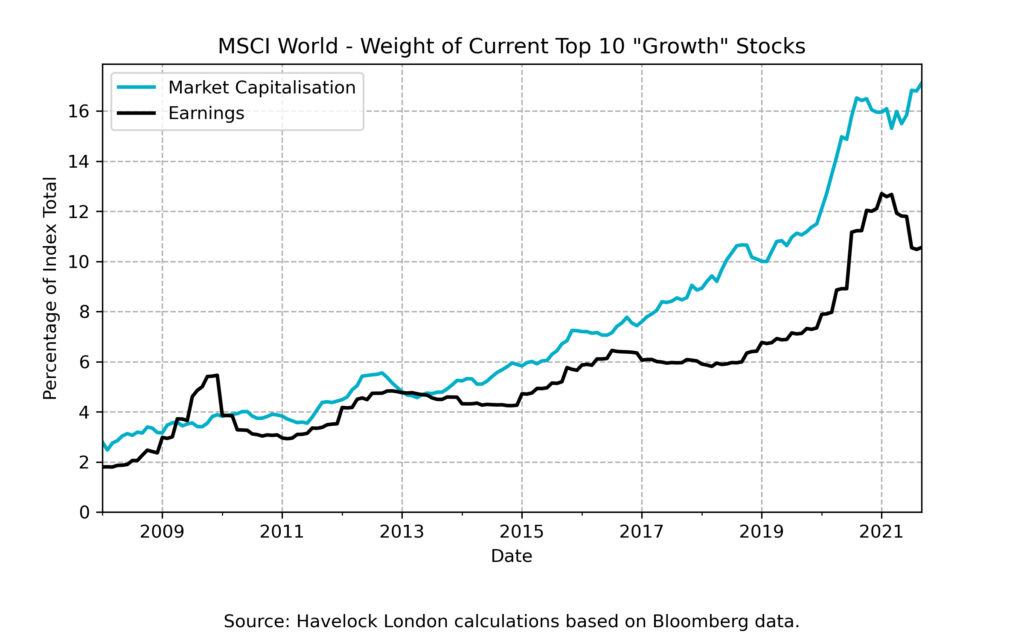

The chart below shows the total market capitalisation of the ten largest “growth” stocks, as defined by the MSCI World Growth index. Their total value is expressed as a percentage of the regular MSCI World index. Hence, if you were to purchase a MSCI World tracker fund you would currently have around 17% of your money invested into these ten large businesses (as an aside this compares to UK stocks having a circa 4% weight in the index).

The second, black, line on the chart shows the percentage of earnings that these ten companies represent. Hence, their earnings, or profits, currently represent around 10.5% of the total earnings of all the companies in the MSCI World index.

How should we interpret this disparity between the current market value of these companies and their earnings?

The share price of a company, in theory, represents expectations about its future cashflows to shareholders. Hence, the disparity between the two measure tells us that the consensus view of market participants is that these ten large businesses will grow their earnings at a much faster rate than the other 1,590 companies in the index. This is possible, but given that they are the largest growth companies, it is surely a tall order?

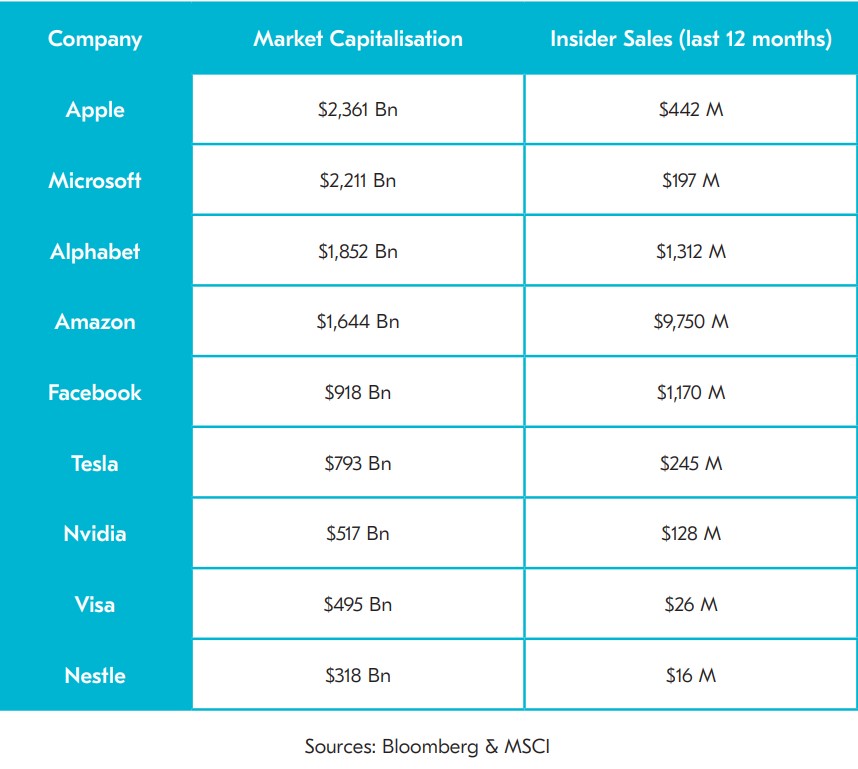

For the curious reader, the table below shows the ten largest constituents of the MSCI World Growth index that were used to produce the chart. Together with their total market capitalisations, the table also includes the total value of shares sold by company insiders in the last 12 months.

Although the value of shares sold by company Directors appear small relative to the companies’ market capitalisations, the proceeds are concentrated in the hands of a very small number of beneficiaries. This represents a transfer of money between purchasers, who will have included retail investors and pension savers, and the people who have an intimate knowledge of these businesses. This leaves me thinking that the empowerment of retail investors could, in fact, be stealing from the poor to give to the rich, rather than the other way around!

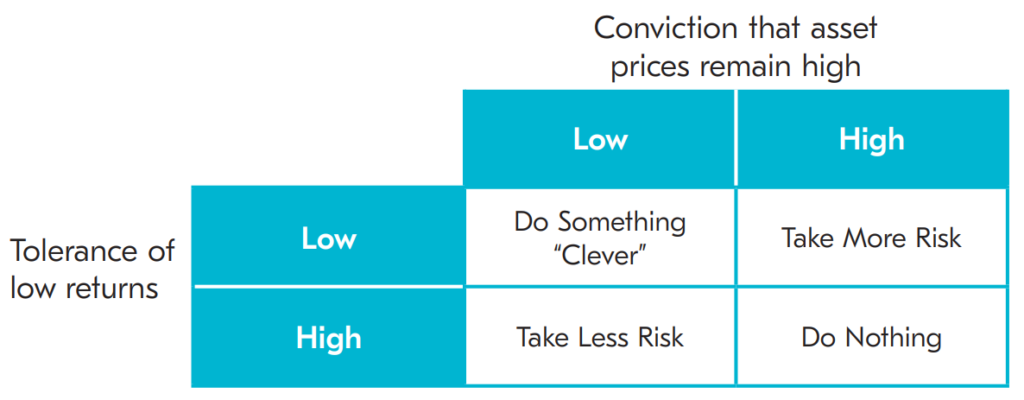

As long-term investors, company valuations matter to us, as a great business will only make for a great investment at the “right” price. We cannot know that these businesses will not live up to current lofty expectations, but our approach is to avoid investing when we think the price paid requires undue optimism. Our core objective is to make sure that our portfolio is robust in a range of future scenarios. By managing the risk of financial loss in this way, we believe we can increase our chances of delivering superior long-term compound returns.